On social media, privacy is no longer a personal choice

Some people might think that online privacy is a, well, private matter. If you don’t want your information getting out online, don’t put it on social media. Simple, right?

But keeping your information private isn’t just about your own choices. It’s about your friends’ choices, too. Results from a study of a now-defunct social media site show that the inhabitants of the digital age may need to stop and think about just how much they control their personal information, and where the boundaries of their privacy are.

When someone joins a social network, the first order of business is, of course, to find friends. To aid the process, many apps offer to import contact lists from someone’s phone or e-mail or Facebook, to find matches with people already in the network.

Sharing those contact lists seems innocuous, notes David Garcia, a computational social scientist at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna in Austria. “People giving contact lists, they’re not doing anything wrong,” he says. “You are their friend. You gave them the e-mail address and phone number.” Most of the time, you probably want to stay in touch with the person, possibly even via the social media site.

But the social network then has that information — whether or not the owner of it wanted it shared.

Social platforms’ ability to collect and curate this extra information into what are called shadow profiles first came to light with a Facebook bug in 2013. The bug inadvertently shared the e-mail addresses and phone numbers of some 6 million users with all of their friends, even when the information wasn’t public.

Facebook immediately addressed the bug. But afterward, some users noticed that the phone numbers on their Facebook profiles had still been filled in — even though they had not given Facebook their digits. Instead, Facebook had collected the numbers from the contact lists innocently provided by their friends, and filled in the missing information for them. A shadow profile had become reality.

It’s no surprise that a social platform could take names, e-mail addresses and phone numbers and match them up with other people on the same platform. But Garcia wondered if these shadow profiles could be extended to people not on the social platform at all.

He turned to a now-defunct social network called Friendster. A precursor to sites like MySpace and Facebook, Friendster launched in 2002. In 2008, the social site boasted more than 115 million users. But by 2009 people began to jump ship for other sites, and in 2015 Friendster closed for good. Millions of abandoned public profiles vanished into the ether.

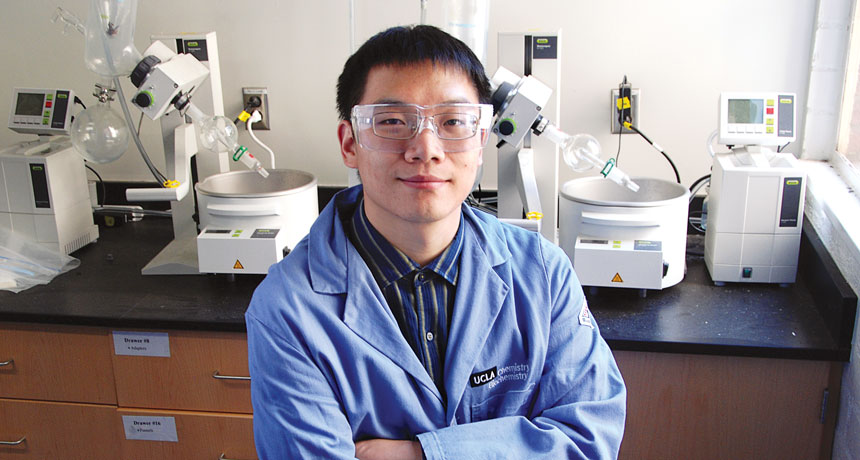

Or did they? The Internet Archive — a nonprofit library — has an archive of more than 200 billion web pages, including Friendster. Garcia was able to use that repository to get data on 100 million public accounts from the social media site. Garcia dug through the records in a process he calls Internet Archaeology, after a satirical video from The Onion in which an internet archaeologist announces that he has, ironically, discovered Friendster. “The time scale of online media is very fast, but it’s still studying things in society that don’t exist anymore,” he explains.

Garcia hunted for patterns in the data. Most people don’t have a random assortment of friends. Married people tend to be friends with other married people, for example. But people also have connections that complicate the ability to predict who’s connected to who. People who identified as gay men were more likely to be friends with other gay men, but also likely to be friends with women. Straight women were more likely to be friends with men.

Using this information, Garcia was able to show that he could predict characteristics such as the marital status and sexual orientation of users’ friends who were not on the social media network. And the more people in the social network who shared their own personal information, the more information the network received about their contacts, and the better the prediction about people not on the network got.

“You are not in full control of your privacy,” he concludes. If your friend is on a social platform, so are you. And you don’t have a choice in the matter. Garcia published his findings August 4 in Science Advances.

This does not mean that social platforms are creating shadow profiles of your social media–averse friends, Garcia notes. But with the information people give to social networks and with the platforms’ computing abilities, they certainly could. To prevent the data being used this way, Garcia only used the most basic, public information. He didn’t predict anything about specific people. He only checked to see if it was possible. Garcia also kept the power of his predictions low and very general. And he was careful to not construct an algorithm that could actually build a shadow profile, to make sure that others cannot misuse the findings.

But the results do show that information from your friends on a social network could accurately predict your marital status, location, sexual orientation or political affiliation — information that you may not want anyone to know, let alone in a social network you’re not even on.

“It’s a good illustration of an issue we have in society, which is that we no longer have control over what people can infer about us,” says Elena Zheleva, a computer scientist at the University of Illinois in Chicago. “If I decide not to participate in a certain social network, that doesn’t mean that people won’t be able to find things about me on that network.”

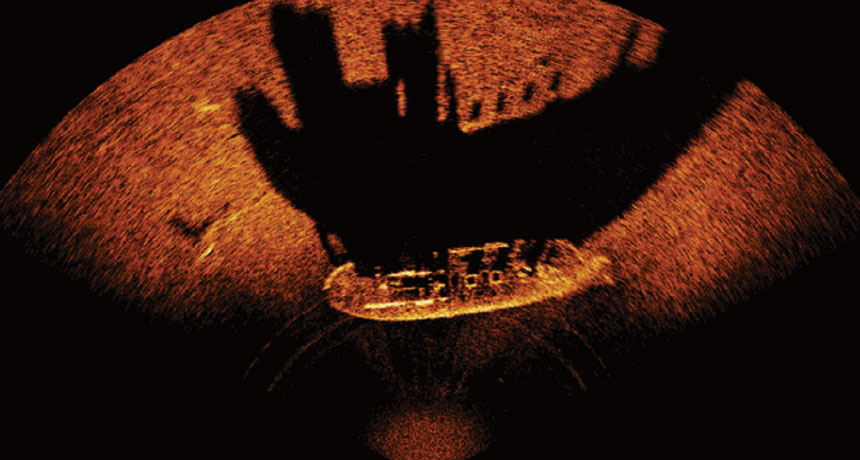

This means we might need to think differently about what privacy means. “We’re used to thinking of having a private space,” Garcia says. “We think we’ve got a room with keys and we let some people in.” But a better image, he argues, might be to imagine ourselves covered in the wet paint of our personal information. If we touch someone else, we leave a handprint. “The more you touch other people, the more you leave on them,” he explains. Touch enough people, and anyone who looks at those people and their paint-covered sleeves will be able to pick out your personal shade of teal.

And because we are no longer in full control of our privacy, Garcia notes, it also means that protecting privacy isn’t something any one person can do. “In some sense it resembles climate change,” he says. “It’s not something you can solve on your own. It’s everyone’s problem or it’s no one’s problem.”