Moon rocks may have misled asteroid bombardment dating

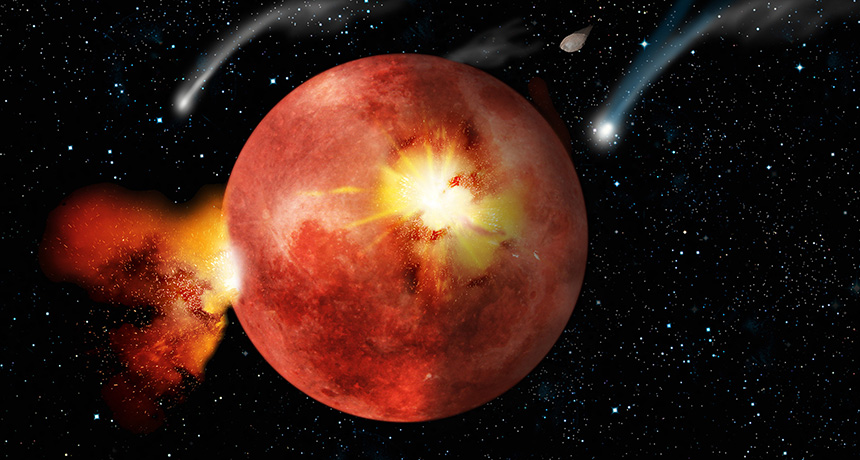

A barrage of rocks hitting the solar system 3.9 billion years ago could have dramatically reshaped Earth’s geology and atmosphere. But some of the evidence for this proposed bombardment might be shakier than previously believed, new research suggests. Simplifications made when dating moon rocks could make it appear that asteroid and comet impacts spiked around this time even if the collision rate was actually decreasing, scientists report the week of September 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Many scientists think that a period of relative calm after Earth formed 4.6 billion years ago was interrupted by a period called the Late Heavy Bombardment, when rocky debris pummeled Earth and the other planets. The moon’s cratered surface holds the best evidence for this event; scientists have measured radioactive decay of argon gas trapped inside moon rocks to date when craters on the moon were formed.

Many of the hundreds of moon rocks analyzed appear to be around 3.9 billion years old. That suggests the number of rocks hitting the moon suddenly spiked at that time — evidence for a Late Heavy Bombardment.

Geochemists Patrick Boehnke and Mark Harrison of UCLA took a second look at the data. Measuring argon from the same rock at different temperatures leeches the gas from different parts of the rock’s crystals; if all those age values align, researchers can be relatively confident they’re getting an accurate age. But many of the lunar samples previously analyzed gave different ages depending on the temperature at which their argon content was measured.

Instead of colliding sharply once and sitting undisrupted, which might give more uniform age data at different temperatures, these lunar rocks were probably tossed around and slammed into other rocks many times, Boehnke says. So assigning one impact age to those rocks might be an oversimplification.

Boehnke and Harrison created a model to simulate how this simplification might affect the patterns seen when scientists looked at the ages of many rocks. The team modeled 1,000 rocks and assigned each one an impact age. Some rocks hadn’t been knocked around and had a clear impact age. Others had been smashed repeatedly, which changed their argon content and obscured the actual impact age assigned by the model.

The model assumed that asteroid collisions decreased over time — that more of the rocks were older and fewer were newer. But still, collision ages appeared to spike 3.9 billion years ago thanks to the fuzziness introduced by the disrupted rocks. So the apparent asteroid increase at that time might just be a quirk due to the way the argon dating data were compiled and analyzed, not an indication of something dramatic actually happening.

“We can’t say the Late Heavy Bombardment didn’t happen,” Boehnke says. Nor do the results invalidate the technique of argon dating, which is used widely by geologists. Instead, Boehnke says, it points to the need for more nuanced interpretation of lunar rock data.

“A lot of data that shows this complexity is being interpreted in a very simplistic way,” he says.

Planetary scientist Simone Marchi says he finds the paper “certainly convincing in saying that we have to be very careful” when interpreting argon dating data from lunar samples.

But there’s other evidence for a Late Heavy Bombardment that doesn’t rely on argon dating, such as dating from more stable radioactive elements and analysis of overlapping craters on the moon, says Marchi, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. He supports the idea of a gentler Late Heavy Bombardment 4.1 billion years ago, instead of a dramatic burst 3.9 billion years ago (SN: 8/23/14, p.13).

Other recent work has also pointed out limitations in argon dating, says Noah Petro, a planetary geologist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., who wasn’t part of the study. Collecting new samples and analyzing old ones with newer techniques could help scientists update their view of the early solar system. “We’re at this point with the moon right now where we’re finding the limitations of what we think we know.”