Year in review: Ozone hole officially on the mend

In a rare bright spot for global environmental news, atmospheric scientists reported in 2016 that the ozone hole that forms annually over Antarctica is beginning to heal. Their data nail the case that the Montreal Protocol, the international treaty drawn up in 1987 to limit the use of ozone-destroying chemicals, is working.

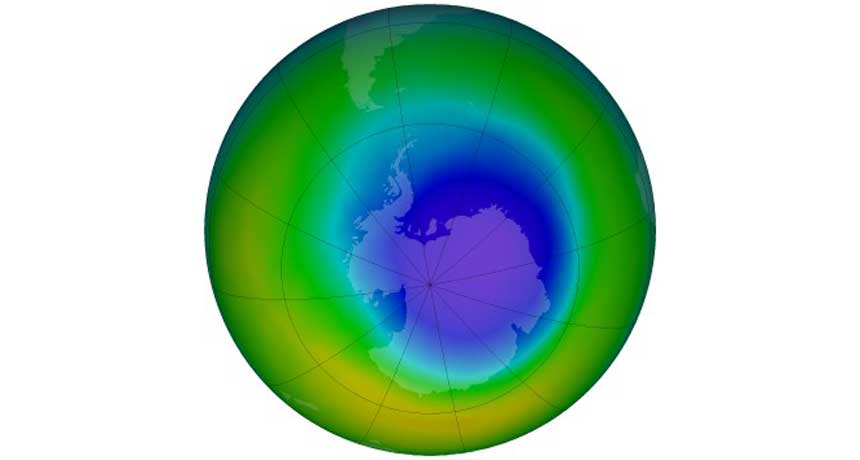

The Antarctic ozone hole forms every Southern Hemisphere spring, when chemical reactions involving chlorine and bromine break apart the oxygen atoms that make up ozone molecules. Less protective ozone means that more ultraviolet radiation reaches Earth, where it can damage DNA and lead to higher rates of skin cancer, among other threats.

The Montreal Protocol cut back drastically on the manufacture of ozone-destroying compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, which had been used in air conditioners, refrigerators and other products. It went into force in 1989 and phased out CFCs by 2010.

Earlier studies had hinted that the ozone hole was on the mend. The new work, reported in Science in June, is the most definitive yet (SN: 7/23/16, p. 6). A team led by Susan Solomon, an atmospheric chemist at MIT, looked not only at the month of October, when Antarctic ozone loss typically peaks, but also at September, when the hole is growing. The healing trend was most obvious in September. Satellite measurements showed that from 2000 to 2015, the average extent of the September ozone hole shrank by about 4.5 million square kilometers, to approximately 18 million square kilometers. Soundings taken by weather balloons over Antarctica confirmed the findings.

CFC concentrations peaked above Antarctica in the late 1990s and early 2000s and have been dropping ever since, says Birgit Hassler, an atmospheric chemist at Bodeker Scientific in Alexandra, New Zealand. Each passing year allows scientists to gather more convincing data. The new study, Hassler says, “makes the whole development of the Antarctic ozone hole healing very transparent and understandable.”

It is a fitting capstone to Solomon’s career. In the 1980s she led a team that proposed that chlorine compounds were to blame for Antarctic ozone loss. She then traveled to the frozen continent to conduct pioneering experiments that measured the accumulating chemicals there. “It’s very humbling now to be 30 years later and be able to say we have a clear fingerprint that the ozone hole is starting to get better,” she says.

Solomon says that public engagement was key to solving the ozone problem, with people coming together to identify an issue that threatened society and develop new technologies to fix it. In that respect, the most successful environmental treaty in history holds lessons for dealing with a much bigger threat, she says — climate change.

To fix the ozone layer, industry stopped using CFCs and similar compounds and replaced them with hydrofluorocarbons. Those chemicals, however, turned out to be powerful greenhouse gases that accelerated global warming. In October, the nations that ratified the Montreal Protocol agreed to expand it to cover hydrofluorocarbons as well (SN: 11/26/16, p. 13).