Brain holds more than one road to fear

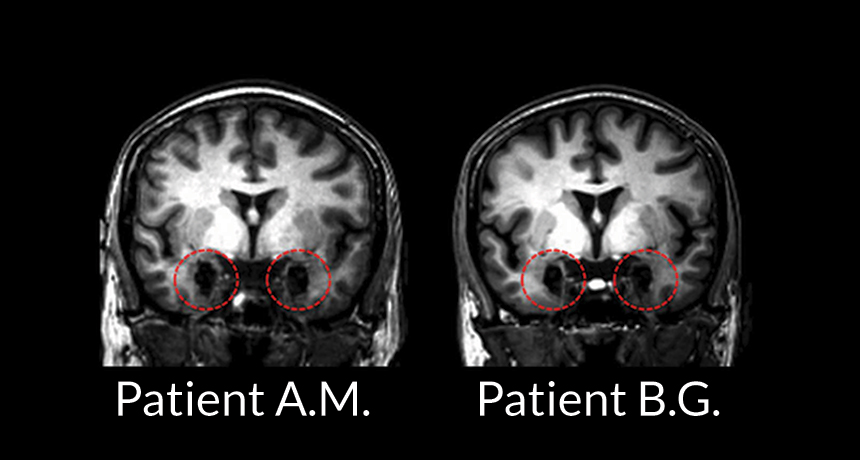

In a pair of twin sisters, a rare disease had damaged the brain’s structures believed necessary to feel fear. But an injection of a drug could nevertheless make them anxious.

The results of that experiment, described in the March 23 Journal of Neuroscience, add to evidence that the amygdalae, small, almond-shaped brain structures tucked deep in the brain, aren’t the only bits of the brain that make a person feel afraid. “Overall, this suggests multiple different routes in the brain to a common endpoint of the experience of fear,” says cognitive neuroscientist Stephan Hamann of Emory University in Atlanta.

The twins, called B.G. and A.M., have Urbach-Wiethe disease, a genetic disorder that destroyed most of their amygdalae in late childhood. Despite this, the twins showed fear after inhaling air laden with extra carbon dioxide (an experience that can create the sensation of suffocating), an earlier study showed (SN: 3/23/13, p. 12). Because carbon dioxide affects a wide swath of the body and brain, scientists turned to a more specific cause of fear that stems from inside the body: a drug called isoproterenol, which can set the heart racing and make breathing hard. Sensing these bodily changes provoked by the drug can cause anxiety.

“If you know what adrenaline feels like, you know what isoproterenol feels like,” says study coauthor Sahib Khalsa, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research in Tulsa, Okla.

After injections of isoproterenol, both twins felt shaky and anxious. B.G. experienced a full-blown panic attack, a result of the drug that afflicts about a quarter of people who receive it, says Khalsa. In a second experiment, researchers tested the women’s ability to judge their bodies’ responses to the drug. While receiving escalating doses, the women rated the intensity of their heartbeats and breathing. A.M., the woman who didn’t have a panic attack, was less accurate at sensing the drug’s effects on her body than both her sister and healthy people, researchers found.

It’s not clear why the twins responded differently, Khalsa says. Further experiments using brain scans may help pinpoint neural differences that could be behind the different reactions.

The results suggest that the amygdala isn’t the only part of the brain involved in fear and anxiety, but there’s more work to do before scientists understand how the brain creates these emotions, Khalsa says. “It’s definitely a complicated question and a debate that’s unresolved,” he says.