Blue leaves help begonias harvest energy in low light

Iridescent blue leaves on some begonias aren’t just for show — they help the plants harvest energy in low light.

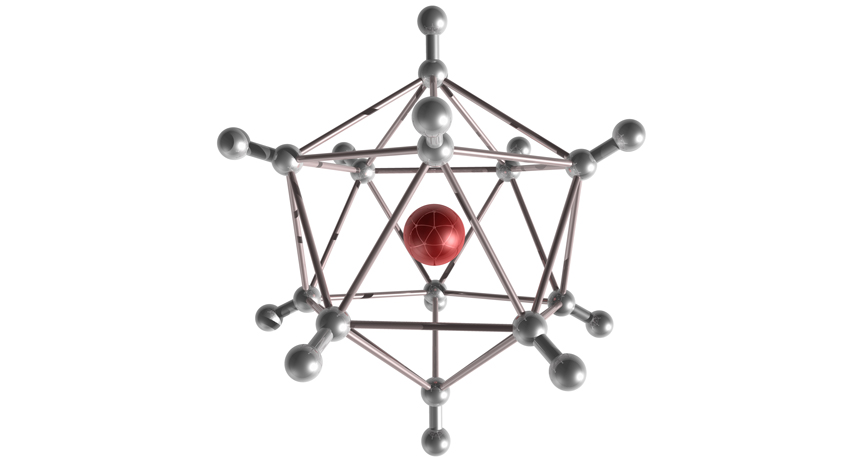

The begonias’ chloroplasts, which use photosynthesis to convert light into fuel, have a repeating structure that allows the plants to efficiently soak up light. This comes in handy for a plant that lives on the shady forest floor. The structure acts as a “photonic crystal” that preferentially reflects blue wavelengths of light and helps the plant better absorb reds and greens for energy production, scientists report October 24 in Nature Plants.

Colors in plants and animals typically come from pigments, chemicals that absorb certain wavelengths, or colors, of light. In rare cases, plants and animals derive their hues from microstructures. In begonias, such tiny, regular architectures can be found within certain chloroplasts, known as iridoplasts. As light bounces off these structures within an iridoplast, the reflected waves interfere at certain wavelengths (SN: 6/7/08, p. 26), creating a blue, iridescent shimmer.

Those structured chloroplasts also offer a survival benefit, the new research shows: They help the plants collect light. In a hybrid of two species — Begonia grandis and Begonia pavonina — the structures enhance the absorption of green and red wavelengths by concentrating these rays on light-absorbing compartments within the iridoplasts. Importantly, the structures slow the light. The “group velocity,” or the speed of a packet of light waves, is decreased due to interference between incoming and reflected light. The slowdown gives the plant more time to absorb precious sunbeams.

“These iridoplasts can basically photosynthesize at low-light levels where normal chloroplasts just simply could not photosynthesize,” says study coauthor Heather Whitney, a plant biologist at the University of Bristol in England. Iridoplasts, however, can’t hold their own in bright light. So begonias also have standard chloroplasts, which provide energy in plentiful sunshine. Iridoplasts act like “a backup generator” in dim conditions, Whitney says.

Other plants have structured chloroplasts, too, so begonias might not be alone in their feats of light manipulation. “Plants can’t really run away from their problems,” Whitney says. Instead, they have to be crafty enough to survive where they stand.